- Home

- Terry Virts

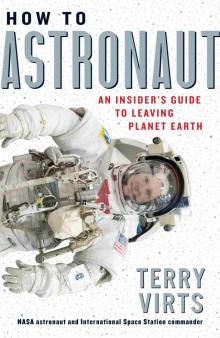

How to Astronaut

How to Astronaut Read online

How To

Astronaut

An Insider’s Guide

To Leaving Planet Earth

Terry Virts

Contents

Introduction: Not Your Father’s Astronaut Book: But He'll Like It Too!

TRAINING

1 FLYING JETS: A Prelude to Flying Spaceships

2 SPEAKING RUSSIAN (ГОВОРИТЬ ПО РУCСКИ): Learning the Language of Your Crewmates

3 PAPER BAGS: Learning Not to Breathe Too Much CO2

4 THE VOMIT COMET: The First Taste of Weightlessness

5 SURVIVAL TRAINING: Preparation for Space Calamity

6 SPACE SHUTTLE EMERGENCIES: The Special Hell Created by Simulation Supervisors

7 CHEZ TERRY: Styling the Hair of a Superstar Crewmate

8 IT’S NOT ROCKET SURGERY: Medical Training for a Spaceflight

9 MOUSE MATTERS: Live Animal Experiments in Space

10 CLOTHES MAKE THE ASTRONAUT: Packing for Six Months in Space

11 ASTRONAUT CROSSFIT: Physical Training for Spaceflight

12 JET LAG (AND SPACE LAG): Adapting Your Circadian Rhythm

LAUNCH

13 DRESSING FOR SUCCESS (AND LAUNCH): A Very Complicated Spacesuit

14 WHEN NATURE CALLS: A Spacesuit Has No Fly

15 THE RED BUTTON: How and Why a Shuttle Could Be Intentionally Destroyed

16 THE RIDE UPHILL: Staying Cool When You’re Blasting Off

ORBIT

17 LEARNING TO FLOAT: How to Cope with Zero G

18 HOW TO BUILD A SPACE STATION: A Painstaking, Piece-by-Piece Process

19 PILOTING SPACESHIPS: Rendezvous, Docking, and Avoiding Space Junk

20 JUST ADD WATER: Space Station Cuisine

21 MAKING MOVIES: An Entire IMAX Movie Shot in Orbit

22 ZZZZZZZZZZ: Sleeping While Floating Is Awesome

23 NO SHOWERS FOR 200 DAYS? NO PROBLEM! Bathing in Space

24 THE GLAMOUR OF SPACE TRAVEL: Going to the Bathroom in Space, Uncensored

25 SATURDAY CLEANING: An Astronaut’s Work Is Never Done

26 WHERE OVER THE WORLD ARE WE? Recognizing Places on Your Planet

27 BAD BOSSES: Silly Rules and Bureaucratic SNAFUs

28 IN SPACE NO ONE CAN HEAR YOU SCREAM: An Ammonia Leak Threatens the Station’s—and the Crew’s—Existence

29 IT WAS A LONG 200 DAYS: Do ISS Astronauts Make Whoopee? (What Everyone Wants to Ask)

30 DEALING WITH A DEAD CREWMEMBER: If a Fellow Astronaut Expires

31 ROBOTIC CREWMATES: Remote Work Outside the ISS

32 PHONES, EMAIL, AND OTHER HORRORS: Communicating with Earth (Slower than Dial-Up)

33 HEARING VOICES: How Psychologists Prepare You for What Spaceflight Does to Your Head

34 PACKAGE DELIVERIES: Receiving, Unpacking, and Repacking Cargo Ships

35 NETFLIX, HULU, AND BASEBALL: In-Flight Entertainment

36 FIGHTER PILOT DOES SCIENCE: Experiments Are the Real Point of the Mission

37 MAROONED: What to Do If You’re Stranded Up There

SPACEWALKING

38 THE WORLD’S BIGGEST POOL: Training Underwater for Spacewalks

39 THE ART OF PUTTING ON A SPACESUIT: And You Thought Launch Was Complicated

40 BRIEF THE FLIGHT AND FLY THE BRIEF: Don’t Fly by the Seat of Your Pants

41 ALONE IN THE VACUUM: The Spacewalk Itself

DEEP SPACE

42 WHAT YOU NEED TO GET TO MARS: A Realistic Look at What It Will Take

43 THE HUMAN BODY BEYOND EARTH: The Physical Toll of Long-Term Spaceflight

44 TIME TRAVEL: Einstein and the Whole Relativity Thing

RE-ENTRY

45 RIDING THE ROLLER COASTER: Re-entry Is Not for Sissies

46 ADAPTING TO EARTH: You Try Walking After Six Months in Zero G

47 TRAGEDY: Being There for the Columbia Catastrophe

48 NO BUCKS, NO BUCK ROGERS: Meeting with Washington Politicians After a Spaceflight

49 SPACE TOURISM: What You Need to Know Before Signing Up

50 ARE WE ALONE? IS THERE A GOD? AND OTHER MINUTIAE: My Take on Some Minor Questions

51 WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN? The Big Picture

Afterword: Isolation: Better on Earth or in Space?

Acknowledgments

Index

Photo Credits

Celebrating 100 days in space during Expedition 42.

Not Your Father’S Astronaut Book

But He'll Like It Too!

This book is a collection of essays, each one on a different subject related to spaceflight. Some short, some long. Some technical, some emotional. Some fact-based, and some purely speculative. Some funny, some tragic. All are written with two goals in mind: to make you laugh, and to make you say, “Wow!” Often.

Many are what you would expect in a book like this. How do you prepare to handle rocket emergencies? How (and why) do you fly jets down here on Earth? Train to be a Crew Medical Officer? Perform all manner of science experiments? Prepare to go outside on a spacewalk? Make a movie in space? Rendezvous two spaceships in orbit? Take a shower in weightlessness?

Planning to leave Earth as a space tourist in the near future? There’s a chapter with all you need to know.

Some essays are hypothetical. What would you do if your rocket engine didn’t light to bring you back to Earth, and you were stuck in space? Hint: You’d have the rest of your life to figure it out. What would you do with the body of a crewmate who passed away? How would you handle tragic news from Earth, or bad news from bad bosses back home? Have people ever had sex in space? I also delve into the most philosophical questions of our time, about God, aliens, time travel, and how to unpack a cargo ship.

One particular chapter in this book was not a part of the original plan. But the editing was finishing up as the COVID-19 global pandemic reached full force, so I added a chapter about surviving isolation in space. It attempts to make a humorous comparison between being stuck in space and being isolated on Earth. The virus has caused so much pain and disruption to our planet, and I hope that this lighthearted take on quarantine and isolation can bring a smile during a time of unprecedented tragedy.

Although this book’s subtitle is An Insider’s Guide to Leaving Planet Earth, there are a few questions you may still have when you’re finished reading it. Which country (or company) will be first on Mars? Is there alcohol in space? How much money do astronauts make and what kind of cars do they drive? Can you play Fortnight in space? Are there guns in space? Will the Orioles ever win the World Series again? So many mysteries.

How to Astronaut is a book about adventure. About exploration. About the unknown. It’s about the best things that make us human, and a few things that make us wish we weren’t. You will come away knowing more about space travel than you knew before you picked this copy up.

I wrote from the heart, in a down-to-earth style. You do not need to be a rocket scientist to digest the concepts here; they are all written so as to require no special knowledge of anything technical, other than curiosity and the desire to learn. This is not a technical manual or book of procedures. I pride myself on not explaining the precise wording of the myriad NASA acronyms you will run across (i.e., “ARED is the NASA acronym for workout machine” is about as technical as I’ll get).

It’s not your typical astronaut fare. But as the saying goes, I’m not your typical astronaut.

To put this book into context, here is a brief description of my career. At the age of seventeen, I left home for the US Air Force Academy, and after graduation at age twenty-one, I began my journey as a jet pilot. I first flew F-16s as an operational pilot in the United States, Korea, and Germany and finally as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base in California. After being selected by NASA as a shuttl

e pilot, I flew on Endeavour in February 2010 for the International Space Station (ISS) final assembly mission, STS-130. We installed the Node 3 Tranquility module as well as the Cupola, a seven-windowed observational module. A few years later, in November 2014, I launched on a Russian Soyuz rocket out of the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, from the same launch pad used by Yuri Gagarin no less. After docking with the ISS, we became part of the Expedition 42 crew. A few months later, a new Soyuz arrived, replacing half of our crew, and I became commander of Expedition 43, until I returned to Earth in June 2015, 200 days after launch.

One final note: I did not use a ghostwriter. Everything here is the work of my own hand. Of course, my publisher gave me a tremendous amount of support in helping to shape and craft this work. But at the end of the day it was written by me. Good, bad, or ugly.

Godspeed (does anyone know what that actually means?) as you jump into this book. I hope many of your questions about space travel will be answered in these pages. Hopefully, others will be stimulated. Although the chapters are laid out in the order of a space mission, from training to launch to orbit to re-entry, they don’t necessarily need to be read in order, so jump around if you want. My greatest desire is that you enjoy How to Astronaut. There won’t be a quiz at the end, so just have fun reading it!

Especially if you are doing it poolside or at the beach. At least six feet away from the nearest fellow sunbather, of course.

Training

Taxiing for takeoff in a NASA T-38 supersonic jet for “Spaceflight Readiness Training.”

Flying jets

A Prelude to Flying Spaceships

There really is no way to completely prepare yourself for spaceflight. You can practice in simulators, study, talk to your fellow astronauts who have been there and done that. But in the end, it’s impossible to prepare yourself emotionally for what is about to happen when the rocket lights and you get launched off the planet in a trail of fire, and then someone turns off the motors and therefore gravity, and you feel like you’re falling (because you are).

Given this, the most important preparation I did before my first spaceflight was flying high-performance jets. Aviation is simply the closest analog we have down here on Earth to prepare astronauts for the rigors of spaceflight. It’s not because of the stick-and-rudder skills of landing, or doing aerial acrobatics, or flying in formation. It’s because of the mental aspects of flying—maintaining situational awareness, staying calm under pressure, making sound decisions in time-critical scenarios, staying “ahead of the jet” mentally, and anticipating several maneuvers into the future, all while zooming along at 500 mph, gas level falling by the minute, with thunderstorms bearing down on your landing airfield.

The ability to do all of these things and remain calm while your pink body—Air Force jargon for any pilot—is on the line is the most important skill any astronaut has. It’s a skill that can’t be taught in a simulator, where there are no real-world consequences. Fast jets are simply the best way for astronauts to hone their steely-eyed, fighter-pilot qualities.

I began my military career flying the T-37 and then the T-38 Talon, the Air Force’s basic and advanced jet trainers, before going on to fly the F-16 Viper for ten years. So when I got to NASA, flying the T-38 again was like riding a bike, even though it had been a decade since my last flight in this training aircraft. But for some of my colleagues, who only had a small amount of time in light aircraft, the T-38 was a huge step up. NASA threw them to the wolves, teaching them the basics of airmanship in the supersonic T-38, a trial by fire. Thankfully, they now send newly hired nonpilot astronauts through an abbreviated military training program in the T-6, a basic turboprop training aircraft that is much slower than a T-38, where they learn the basics of airmanship and flying. These astronauts will never be T-38 aircraft commanders—they will always fly in the rear cockpit as supporting aircrew—but they play a crucial role, working with the pilot in the front cockpit to fly their missions successfully, and most importantly, training to get ready for spaceflight.

There are a few important skills for new crewmembers to learn. First, and paramount, is to sound cool on the radio. There really is nothing worse than someone sounding confused, or scared, or babbling on and on when they try to call the tower for permission to take off. The best advice I gave the new guys was to always sound slightly annoyed that you have to be bothered to even key the microphone to talk. You don’t want to sound arrogant or like a total jerk, but you need to have an “OK, I’ve got things to do and let’s get on with it” tone. Years later a Hollywood producer gave me the same advice when I was doing a voice-over for a video. He told me that I sounded too relaxed, and I needed to be annoyed to sound more cool. Also, new aircrew need to rehearse in their mind what they’re going to say before actually talking. Clear and Concise with a touch of Annoyed is a good formula for success when talking on the radio. In the fighter community we used to joke that if we were about to crash, we would have to sound good, right up until impact. We had a reputation to uphold.

Compared to an F-16 or other, lesser fighters, the T-38 is pretty simple. As a shuttle pilot, I found the Talon to be about as complicated as a single shuttle system. For example, the shuttle’s hydraulic system, or its computers, or its main engines each seemed to be roughly as challenging to master as the overall T-38. Still, I needed to study. Airplane systems. Normal procedures. Emergency procedures. Instrument flight rules and air traffic control procedures. Weather. Survival techniques. There’s about a month of ground school that new guys go through, and annual refreshers for the old guys. Although it’s a simple jet, there’s still a lot to know.

Next comes the flying. You have to get used to strapping yourself to an ejection seat, putting on a helmet that is hard to breathe through, sitting in a 1960s-era cockpit that smells like a combination of jet fuel/dirty laundry/teenager’s room, accelerating your body forward with afterburners, like stepping on the gas pedal, and getting smashed down into the seat when you turn the airplane, like driving fast around a corner, otherwise known as pulling g’s. You have to be able to cover the inside of the canopy with a bag and fly based on instruments only, simulating bad weather. You have to get used to an incredibly high roll rate; the T-38, with its stubby wings, can actually do two complete rolls per second, though I was rarely inclined to do so.

You have to keep track of your gas. “Minimum fuel” is a term used to tell air traffic control that we were out of gas and needed to land ASAP. In the T-38 we used to say that we took off with minimum fuel. Those short wings don’t hold any gas and those 1950s-era jet engines burn a lot of dinosaurs, so you’re aware of—and low on—gas from the minute you take off. What’s more, flying in Texas and the American South means flying around thunderstorms. Lots of them. I remember being taught as a student that there is no peacetime mission that requires flying through a thunderstorm, and based on some of the damage I’ve seen those monstrous storms do, I agree. However, in the summer they’re everywhere, so a lot of your brain cells are taken up with avoiding them while getting to your destination with some gas in the tank.

NASA astronauts fly different T-38 missions, most involving basic navigation to an airport, usually 400 to 600 miles away, doing practice instrument approaches, landing, and then flying back to Ellington Field, our home base in Houston. There are several key criteria to evaluate when selecting which airport to fly to. My top priority was availability of good BBQ or other food—along with minor details such as weather, their ability to service T-38s with the air start unit required to start our jet engines, government contract fuel, a 7,000-foot or longer runway, etc. These out-and-back missions give astronauts a chance to work on soft skills such as crew coordination and situational awareness. Sometimes they go out and do acrobatics, which is somewhat useful to prepare for the sensations of weightlessness, though in truth nothing can fully prepare you for that. During the space-shuttle era we used to fly to Cape Canaveral or out to El Paso and the White Sands Missile Range

to do practice shuttle approaches. The main aircraft for this was a modified Gulfstream G2, but we occasionally did these extreme approaches in the T-38, which was similar to a 20-degree dive bomb attack that I used to do in the F-16.

Sometimes, however, things didn’t go as planned. And that’s precisely what makes the T-38 so valuable; shuttle and station training in controlled simulator environments could not put your butt on the line to get the “pucker factor” up. One day when taking off at dawn, I hit a flock of birds, exploding the left engine. I circled back for an emergency landing on the remaining good engine. It was the shortest flight that I’ve ever recorded in my logbook—and probably the most heartbeats per minute of any flight I’ve ever had. I’m still thankful that in my backseat that day I had Ricky Arnold, one of the best mission specialists NASA ever had. One night when I was flying to Midland, Texas, the airport was hit with a rogue haboob dust storm, shutting the airfield down, and we had to fly 100 miles to the next nearest airport, sucking seat cushion through our sphincters and praying, “God, please let us make it to Lubbock.” Guess who was my backseater on that day? His initials are RA.

My flying career is full of stories like these: almost running out of gas in the F-16 at Eglin AFB; finding a runway closed down upon arrival at Tallahassee and barely making it to Tyndall AFB; having my wingman lose his engine while flying over Iraq in the single-engine F-16; almost flying into a mountain on my first-ever LANTIRN (Low Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared at Night) flight—the computer saved my life at the last second; being disoriented and pulling my F-16 straight up at night (thankfully it wasn’t straight down—I’d rather be lucky than good); I could go on and on. I’ve had plenty of close calls during my twenty-seven years of flying fast jets.

Although there is no direct correlation between high-performance aviation and living on the space station for six months, the possibility that some unexplained emergency could strike at any moment is what keeps you on your toes, and that is the best possible mental preparation for spaceflight.

How to Astronaut

How to Astronaut